emerging-mind.org, eJournal ISSN 2567-6466

Email: info@emerging-mind.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

gerd@doeben-henisch.de

(August 11, 2022, latest change: August 14, 2022)

CONTEXT

This Text is an example located in the List of examples for the raspBerry Pi experimental board.

My Real Story: Start a raspBerry Pi board

(Last change: 14 August 2022, 08:23h)

Triggered by an interesting master thesis of a student writing about a Robo-Car which is using a raspBerry Pi experimental board, I decided to start myself with some experiments.

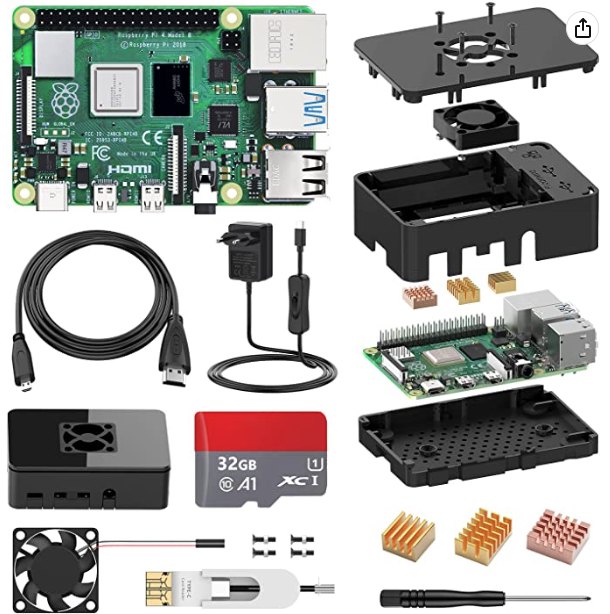

Instead of starting directly with the raspBerry Pi organisation [1] I checked the internet and came up with a package like this: STUUC Raspberry Pi 4 Model B 8GB Ram with 32GB Memorycard, Raspberry Pi 4B Kit with Quad-Core A72 supporting Dual Display 4K/WiFi 2.4G.5G,LAN 1000Mbps/ BT 5.0/USB3.0 all Parts included.

This was all I had; no further explanations. To put all these parts together, purely mechanically, wasn’t such a problem. But this is not what you want. You want a working computer. With the following steps it worked out nicely:

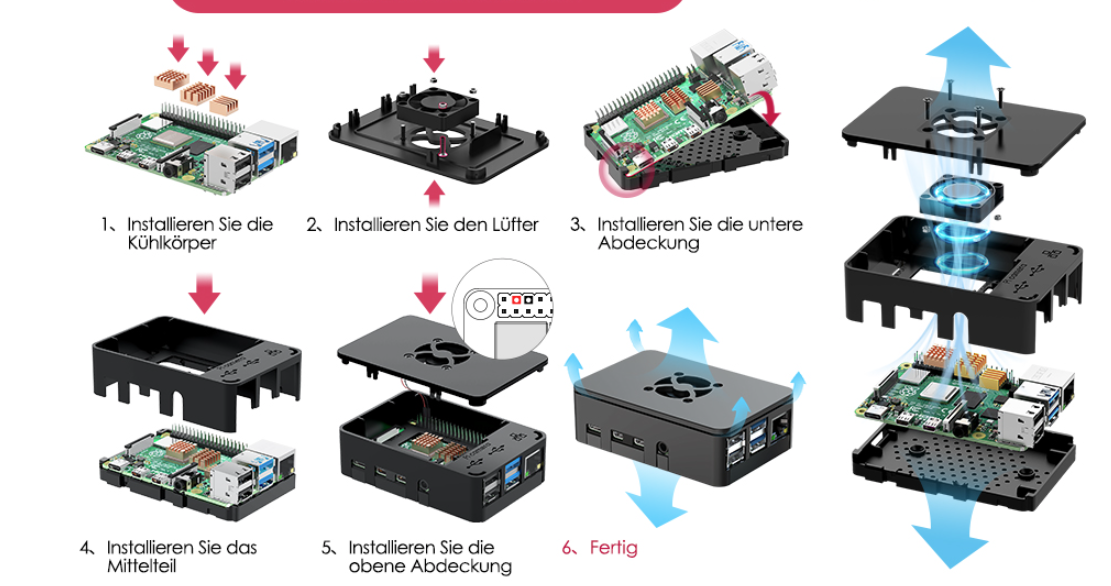

- I put the cooling elements (the ‚heat sinks‘) on the determined parts by pressing them onto the surface, after I have pulled the protective layers off.

- I put the board into the ground cover.

- Then I put the micro-SD card (32 GB) into a small slot left on the board (there is only one) with the inscriptions of the SD card below (otherwise it will not enter the slot).

- Then I inserted the power supply in the USB-C slot, the screen with the HDMI cable to the left micro HDMI slot, the mouse and the keyboard to the 2 left USB-2 slots.

- Then I attached the middle cover on the board.

- Then I switched the experimental board on.

- The screen became active but the text appearing on the screen told me, that the software is too old, and this message started to repeat …

- I pulled the micro SD card out again, transferred it with an SD-card adapter into an old SD-card reader, connected it to my unix-machine (a windows machine would also work) and activated the raspBerry site where the raspBerry Pi software is described.[2]

- From this site you can download the ‚Raspberry Pi Imager‘ which is a very nice program. If You start it (linux as well as windows) you can download the newest version of the raspBerry Pi operating system on your SD card, pull them out and insert it again in your raspBerry Pi board.

- Starting again with the new version, now it worked fine. Connected to the internet via Ethernet or Wlan you can update everything and then you can start working.

- With the free USB-3 connectors you can connect other SD-card memories or even large USB-drives … and much more.

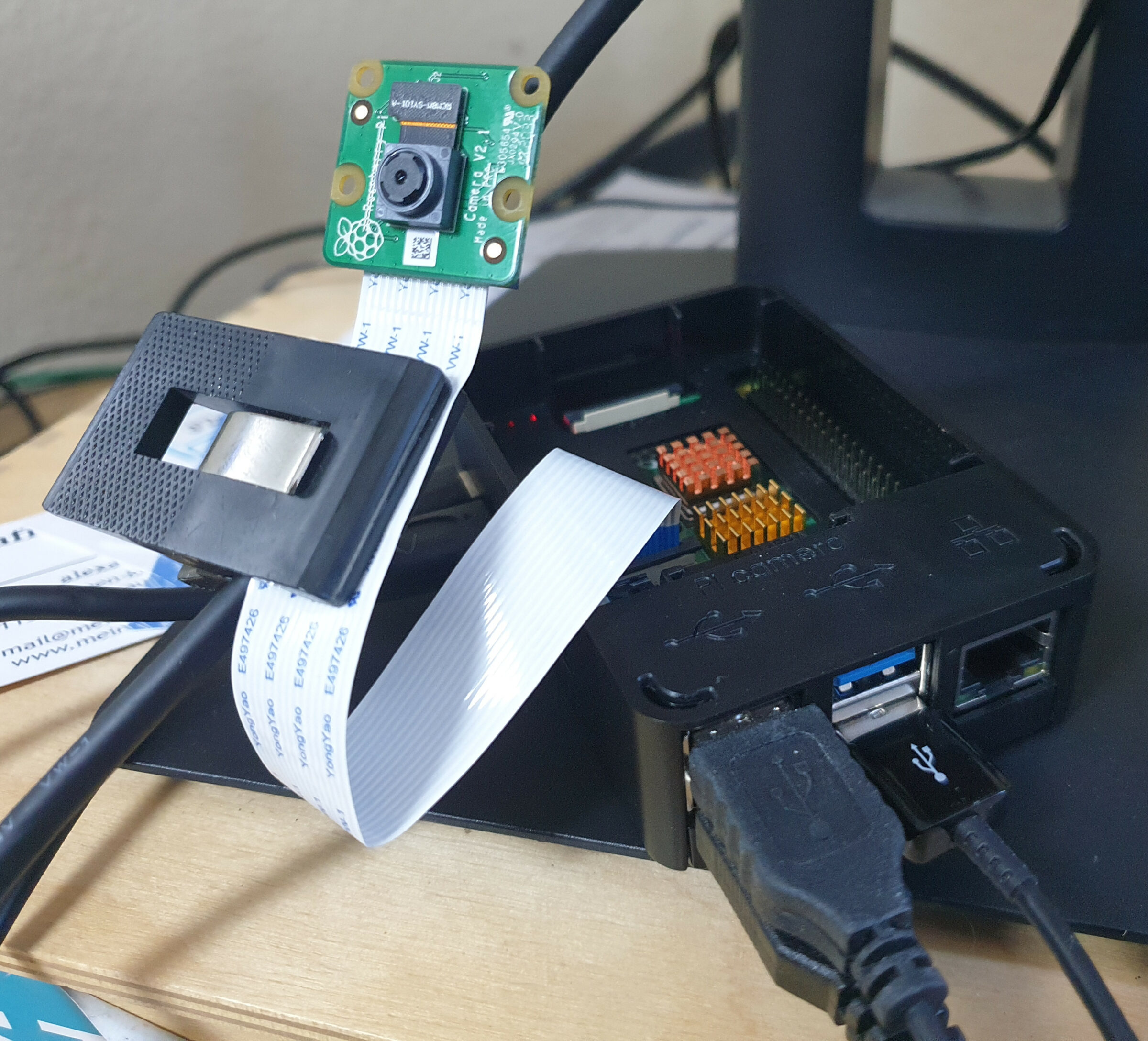

Adding a camera

For the experiments-chapter I will need a camera. Here you can get first information about the raspberry Pi’s cameras. I decided to take the new camera which offers a lot of capabilities.

The specialty of the raspberry Pi’s cameras is that these are fully integrated in the hardware and software of the raspi.This enables completely new applications compared to a ’normal‘ camera which is only attached by an USB connector. This full integration is possible because there exists a whole bunch of software called in the older version ‚raspicam‘, now ‚libcamera‘, which can be used to work with the signals of the camera. The original sources for the camera are written in C++, but the user can interface with the camera by so-called camera-apps which offer complex functions for direct use, and one can write own camera-apps. But because the most used programming language on the raspi is the programming language python, there existed since the beginning a python library called ‚picamera‘ provided from the ‚outside‘ of the raspi development team. With the publication of the new raspberry Pi processor accompanied by a new version of the operating system (linux) called ‚bullseye‘ the old python picamera library doesn’t work any longer. One can still use it, but the future has another direction. The new ‚philosophy‘ of the rasp development team is nicely described in this ‚readme document‘ attached to the new version of the camera software called ‚libcamera‘:

„A complex camera support library for Linux, Android, and ChromeOS

Cameras are complex devices that need heavy hardware image processing operations. Control of the processing is based on advanced algorithms that must run on a programmable processor. This has traditionally been implemented in a dedicated MCU in the camera, but in embedded devices algorithms have been moved to the main CPU to save cost. Blurring the boundary between camera devices and Linux often left the user with no other option than a vendor-specific closed-source solution.

To address this problem the Linux media community has very recently started

collaboration with the industry to develop a camera stack that will be open-source-friendly while still protecting vendor core IP. libcamera was born out of that collaboration and will offer modern camera support to Linux-based systems, including traditional Linux distributions, ChromeOS and Android.“

To write a completely new camera software in python is not a simple task. Therefore it needed some time to develop it and it is still not completely finished. But, luckily, the first experimental releases are there and do already function to some extend. While the messages from the development team in November 2021 have been rather announcements only, the massages from February 2022 sound differently. Now a new — yet still experimental — software is available by download from the github server. The new name of the old picamera library is ‚picamera2‘ and it is developed now by the raspi development team directly. Here you can find a download for the picamera2 document, which describes the whole library with installation descriptions.

Here you can look to a 10s video taken with the new camera modul 2 with the new — still experimental — python library picamera2:

from picamera2 import Picamera2

picam2 = Picamera2()

picam2.start_and_record_video(„test.mp4“, duration=10)

configure-tool

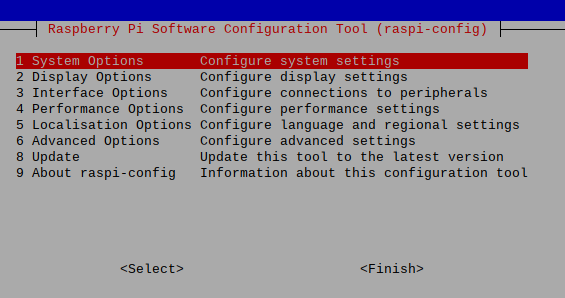

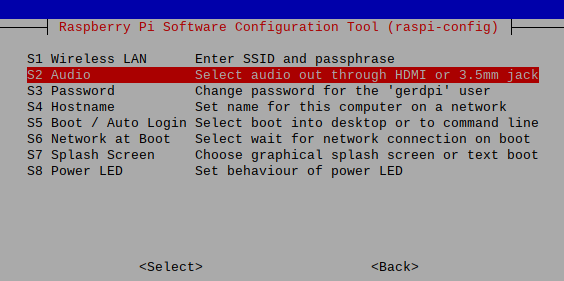

The simplest way to configure the raspberry Pi after the installation is to call the rasp-configure tool by typing into the shell:

gerdpi@raspberrypi:~ $ sudo raspi-config

Then the following screen will show up:

If you will use the audio-jack for your headphones instead of the loudspeaker of your screen you can select on the main screen 1. System options and then

you can select S2 Audio to make your choice.

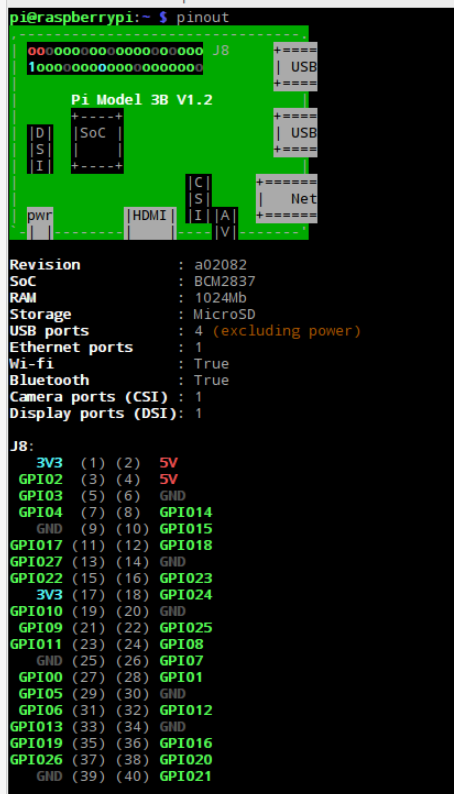

GPIO-settings

If you want later define some settings on the general input-output (GPIO) you can do this. Here is the GPIO outline:

COMMENTS

[1] See raspBerry Pi organisation: https://www.raspberrypi.com

[2] raspBerry Pi organization, software: https://www.raspberrypi.com/software/ or here, more simpler: https://projects.raspberrypi.org/en/projects/raspberry-pi-setting-up/1